- FEATURE

- |

- MERGERS & ACQUISITIONS

- |

- FINANCIAL

- |

- MARKETING

- |

- RETAIL

- |

- ESG-SUSTAINABILITY

- |

- LIFESTYLE

- |

-

MORE

The last two weeks have brought two eye-catching stories to the luxury retail sector. Though seemingly unrelated, both events shed some light on the question: "How can luxury goods be sold effectively?"

First off, DeWu has become a powerhouse for selling luxury items. Bloomberg sources report that in the first half of this year, DeWu's sales of Louis Vuitton products increased by 11% to 2.6 billion yuan, about 358 million USD. With LV's domestic sales already at about 2.5 billion USD, adding DeWu’s figures means LV’s total revenue in China could have risen by over 14%.

Bloomberg also noted that other luxury brands like Dior, Hermès, Chanel, and Prada enjoyed significant sales boosts on DeWu in the first half of the year, all achieving double-digit growth from the year before.

Secondly, Wuhan saw a massive luxury discount sale earlier this month. Wushang MALL, Wuhan Henglong Plaza, and Wuhan SKP all launched promotions for the Qixi Festival, sparking a surprisingly vibrant market response. Leading brands saw long lines and some stores even sold out completely.

These two cases—from online platforms to physical stores, appealing to both trendy youth and traditional department store shoppers, and from central China to the national scene—collectively demonstrate that if price concerns are addressed, Chinese consumers remain enthusiastic about splurging on luxury goods.

On DeWu, a black Chanel CF bag is listed at 54,679 yuan—25,000 yuan less than in-store prices. The always-out-of-stock Chanel 22 bag is almost 7,000 yuan cheaper, and the popular LV Carryall is being offered at roughly 20% off.

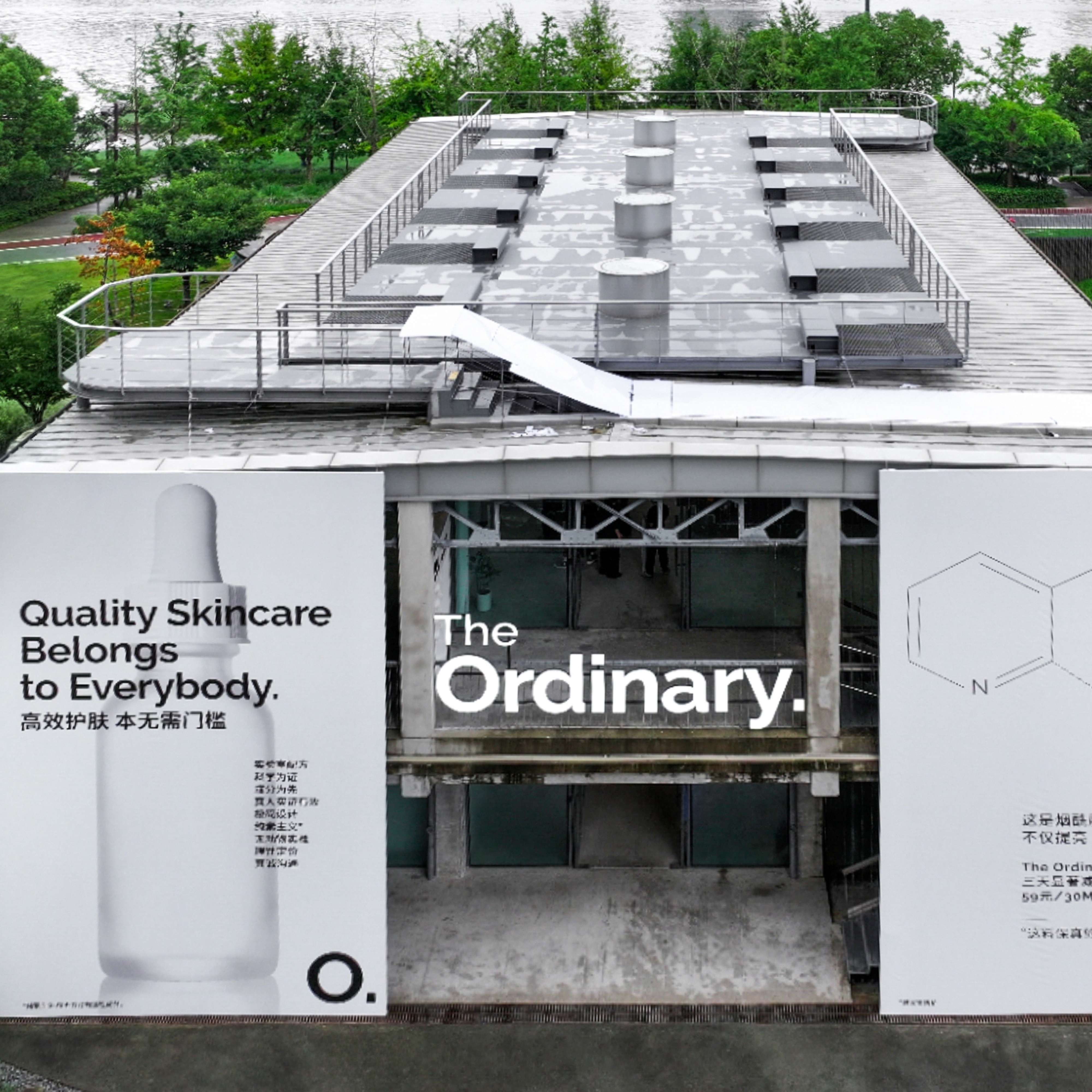

Even though most of DeWu’s luxury items come from other channels, fashion fans continue to crowd the platform, driven mainly by these price cuts.

In Wuhan’s promotional war, the three malls offered basic deals like cashback on spending over a thousand yuan and bonus points, which, while not new, effectively allowed consumers to save significantly. They got deals on authentic products from Gucci, LV, Loro Piana, Dior, Prada, Van Cleef & Arpels, Cartier, Bulgari, and Tiffany—even Hermès—at effective discounts through legitimate channels.<